http://jeremydu

Highway Robbery: The Mask of Knowing in Assassin of Secrets

To play with the phrasing of Dr Knowd’s assessment of Charles Highway, Quentin Rowan has, I think, used others’ literature ruthlessly for his own ends (if you haven’t followed this story, please see my last post). But in doing so, he did, curiously, also create something that had ‘a life of its own’, and to adopt a pseudo-academic tone, what one might call a mask of knowing and an unearned, one could say, automatic resonance.‘“For example. In the Literature paper you complain that Yeats and Eliot... ‘in their later phases opted for the cold certainties that can work only outside the messiness of life. They prudently repaired to the artifice of eternity, etc. etc.’ This then gives you a grand-sounding line on the ‘faked inhumanity’ of the seduction of the typist in The Waste Land – a point you owe to W. W. Clarke – which, it seems, is just a bit too messy all of a sudden. Again, in the Criticism paper you jeer at Lawrence's ‘unreal sexual grandiosity’, using Middleton Murry on Women in Love, also without acknowledgement. In the very next line you scold his ‘overfacile equation of art and life.’”

He sighed. “On Blake you seem quite happy to paraphrase the ‘Fearful Symmetry’ stuff about ‘autonomous verbal constructs, necessarily unconnected with life’, but in your Essay paper you come on all excited about the ‘urgency… with which Blake educates and refines our emotions, side-stepping the props and splints of artifice’. Ever tried side-stepping a splint, by the way? Or educating someone urgently, for that matter?

“Donne is okay one minute because of his ‘emotional courage’, the way he seems to ‘stretch out his emotions in the very fabric of the verse’, and not okay the next because you detect... what is it you detect? – ah yes, a ‘meretricious exaltation of verbal play over real feeling, tailoring his emotion to suit his metrics’. Now which is it to be? I really wouldn’t carp, but these remarks come from the paragraph and are about the same stanza.

“I won’t go on... Literature has a kind of life of its own, you know. You can’t just use it...ruthlessly, for your own ends...”

Apart from taking the piss out of the inevitable academic study of this book that I think will soon appear, what do I mean by that? Let me try to explain, in terms which I hope are not pseudo-academic, self-serving or forgiving, but an honest attempt to understand why I liked the book so much, and why it ‘worked’, at least for a time. Since the plagiarism in Assassin of Secrets has come to light, I’ve seen remarks from several people wondering how on earth it was not spotted earlier, by his agent, his editors, reviewers, or Greg Rucka, Duane Swierczynski and myself, all of whom praised the book and are now angered at having missed what it was. I haven’t gone through every line of the book, but it seems clear that the vast majority of it, pretty much down to every paragraph, was stitched together from other works: at least a dozen in total. But even if you weren’t familiar with the works he stole from, some have asked, surely it must have been obvious that the book was not original because it would have been totally incoherent?

Well, no. It is a coherent novel. The plot is not its driving force, as it might be in a crime story, and in many ways it read to me like a collection of set scenes, which of course was what it was. But that feeling – absent the knowledge that it was plagiarized – was part of its charm. I don’t believe that the book was a post-modern experiment to expose the publishing industry or anything of that sort, as some have inevitably and rather tediously suggested, simply because ruining your own career and having to pay your advance back in the process is not all that fun an experiment. Was Richard Condon doing the same when he plagiarized I, Claudius in The Manchurian Candidate? Or was he, more likely, simply plagiarizing and hoping nobody would spot it, as indeed in that case nobody did for many years. (I don’t know if anyone has examined the book in more detail since 2003, but I suspect there may be a lot more plagiarism in it, and probably in Condon’s other novels, too.)

But a great part of the appeal of Assassin of Secrets, to me anyway, was what I felt to be its post-modernism, albeit in a very different way. It reminded me of several other novels – sadly, not the ones he plagiarized! It reminded me in parts of Cockpit, Jerzy Kosinki’s 1975 novel about a former spy called Tarden, which contains a lot of dazzling writing but reads as fragmentary excerpts. This is perhaps not all that surprising, as Kosinski has also been exposed as a plagiarist (long after he was published, and won many awards), and Cockpit is now thought to have been a compilation of pieces by several unknown writers Kosinski commissioned and then assembled, partially helped by a young Paul Auster.

It also reminded me in parts of David Lynch’s Mullholland Drive. Like Cockpit, that film is compelling not for its plot, which is unfathomable or non-existent, but in the way it plays with our memories of and feelings for genre conventions. Both Cockpit and Mulholland Drive feel like dreams, where narrative rules are abandoned, leaving dead-ends that allow the reader or viewer to step in and find their own resonances. It also reminded me in parts of Inception, which does have a coherent plot (I think) but does much the same. At one point in that film, Cobb and his team have to infiltrate a guarded clinic – that’s plot. But Christopher Nolan could have placed that clinic anywhere, and the plot would have been the same. He decided to place it in a snowy mountain fortress, I think so he could have fun exploring, almost in isolation of the plot, our memories of and expectations of a James Bond film.

The plot of Assassin of Secrets was more coherent than Cockpit or Mulholland Drive, but not as coherent as Inception. It worked, and held the attention, but it was not the chief appeal: it was understood that it was a vehicle for spy shenanigans around the world. The book also reminded me of Tunc and Nunquam, two linked novels by Lawrence Durrell that play with spy thriller conventions, and James Bond, and leap about all over the place. There is a plot, but it’s not what I primarily find enjoyable about those novels, the latter of which, incidentally, features a snowbound clinic, and of which The Observer’s critic wrote: ‘There are times when one wonders if one isn’t reading some unholy coupling of Swinburne and Ian Fleming.’

It was the style that I liked most about Assassin of Secrets. That style was predominantly taken from the American spy novelist Charles McCarry, at least five of whose novels Rowan plagiarized: The Tears of Autumn, Christopher’s Ghosts, Shelley’s Heart, The Last Supper and Second Sight. I’ve read the first two of those mentioned several years ago, and remember next to nothing about them other than that the protagonist is a CIA officer who is also a poet, that I enjoyed them, and that the prose was wonderful. Much of what I admired in Assassin of Secrets, I now realize, was McCarry’s prose, which looks to take up roughly half the book, although that may not have been the case with the draft his agent submitted to publishers. On July 2 2010, shortly after he was offered a two-book deal by Little, Brown, Rowan wrote to me via Facebook:

‘Now I s’pose I wait for them to summon me to sign some contracts and then I’m working with the editor. Can’t remember if I told you, but besides changing the title, he wants me to change a few scenes he thought too Bond-like. If they’re really going to stick me with this new title, I’m thinking of proposing ‘An Enemy of War’ instead. Even so, it’s quite forgettable.

Trying to take it easy now and celebrate but mind is mostly racing miles ahead of me. Luckily, I’ve already started the second book...

All the Best,Quentin’

‘Too Bond-like’ is quite something, as most of the published novel that is not plagiarized from McCarry is plagiarized from Bond novels. Presuming he was telling me the truth, I wonder how much Bond was in his original submission to his agent. But perhaps this was a lie designed to put me off the scent, although it seems an odd way to do that. We had discussed our favourite authors in the genre before. On May 4 2010, he had emailed me:

‘Have you tried Adam Diment? or James Dark (Don’t think that was his real name, but his spy is named Mark Hood). I’ve found them both pretty enjoyable, though a little light-weight. One thing I’ve found in my research is that there really aren’t that many American spy novelists who are any good. Perhaps only Charles McCarry. Though I suppose there are good American thriller writers, their prose is usually slightly awful. Take Robert Ludlum, for example.’I have read Adam Diment and James Dark (though please don’t test me on them), and told him so. I also told him that I had read some McCarry and enjoyed it, but that I hadn’t read all his work – perhaps at this point he decided to add more McCarry into the book.

Quentin Rowan’s emails to me were, either accidentally or by design, well aimed. I share his view of Ludlum, who of course he also plagiarized in Assassin of Secrets. I think it may be that he knew I would share these views, as I have probably spouted them somewhere online in the last decade, and he was simply parroting them back at me. Or he may have genuinely felt this way – in which case why did he plagiarize Ludlum, if he thought his prose was ‘slightly awful’? Well, not all of Ludlum’s prose is that, of course. Ludlum has sold over 200 million books, so he was doing something right. And I think that was primarily two things: premise, and pace. By the first, I mean Ludlum had some terrific premises, most notably that of The Bourne Identity, of a government assassin who was forgotten who he is and is being chased by his desperate employers. As I explored in this essay, it is clearly inspired by Ian Fleming, who I think in turn may have taken the premise from two previous writers. But Ludlum made it his own, and made it exciting. On pace, Ken Follett has written that a story ‘should turn about every four to six pages’. McCarry does not subscribe to that idea; Ludlum sometimes has several major turns in one page. These are often rendered in hackneyed and laboured prose and signalled by internal dialogue in italics with exclamation points, but they have their own intensity that sweeps you up and keeps you reading.

And Ludlum didn’t always write in hackneyed prose. Those bits tend to stand out and irritate me, but he also wrote plenty of vivid and evocative descriptions, sometimes overly florid but sometimes judged just right. He was notorious for making mistakes about guns, but his fight scenes are usually gripping. He was also extremely prolific, perhaps making detection seem less likely. It looks to me as though Quentin Rowan took several passages from Ludlum that he thought fitted his purposes. They provided his hero with some muscularity – the stereotypical secret agent who can kill everyone in the room using a toothpick. Assassin of Secrets also reminded me of Trevanian, incidentally, who parodied this sort of thing brilliantly in Shibumi, The Eiger Sanction and The Loo Sanction, often in such a deadpan style that it was not noticed.

Yes, it reminded me of a lot of books, and the wrong books to boot – but there are a lot of books out there. His protagonist, Jonathan Chase, is (was?) an amalgamation of attributes: like many of Ludlum’s protagonists, he is determined, fit, and repeatedly evades death with consummate skill, often in close combat with opponents. This came back into fashion with the film version of The Bourne Identity in 2002, meaning that segments taken from old Ludlum novels now seem up-to-the minute even when, perhaps especially when, transferred into a Cold War setting. Jonathan Chase is also up against a vast villainous organization who meet in a secret headquarters in a Casablanca market accessed via a steel passageway. If you’ve read Raymond Benson’s 1999 James Bond novel High Time To Kill, you may recognize that this is where he took that from, but I read that book in 1999 and interviewed Raymond Benson about it, and didn’t notice. Rowan, relocating all the action to the late Sixties, combined Benson’s scene with one from McCarry’s Second Sight. Rowan’s villain, The Mirza, looks precisely like Benson’s villain, Le Gérant, and speaks many of his lines verbatim. But he also resembles McCarry’s villain Yeho, and speaks many of his lines verbatim. Likewise, Rowan’s character Neville Scott is a mix of McCarry’s character Horace Christopher and Benson’s character Dr Steven Harding.

McCarry’s characters are much more recognizably realistic than Benson, Ludlum or Gardner’s – he was writing a different sort of spy novel, and it doesn’t contain fist-fights or underground lairs, but is rather more concerned with lie detector tests and elaborate deception operations that play out like chess games. Rowan took elements of both, and combined them into a stew that in hindsight may seems obvious (especially if you were not fooled originally!), but which I genuinely found not just coherent, but compelling. Here’s an example of how he did it, with a passage from page 9 of Assassin of Secrets in which an American agent, Number One, is drawn by a beautiful woman on a train to her compartment, whereupon she attacks him:

‘With a shout, he delivered a kick to the blond woman’s chest, knocking her back. The blow was meant to cause serious damage, but it landed too far to the left of the sternal vital-point target. Number One was momentarily surprised that she didn’t fall, but he immediately drove his fist into her abdomen. That was his first mistake – mixing his fighting styles. He’d been using a mixture of karate and traditional Western boxing, whereas the female had picked a system and stuck with it. He kept on, though, lunging away, and smelling her stinking Je Reviens perfume, but he knew these sensations were only a dream. In reality they were floating in a skiff down the Seine, listening to a tinny phonograph record of a girl singing in French. How beautifully the girl sang, how the river smelled of the flowers that turned its torpid waters into perfume, how much like his own mind and voice were the mind and voice of this chanteuse! It was uncanny.

Someone seized his lower lip and twisted. The pain changed his idea of where he was. His right eye focused, briefly, and he glimpsed the blond woman’s eyes. She was on top of him now, thrusting her forearm into Number One’s neck, exerting tremendous pressure on his larynx. With his right hand, the American fumbled in his pants pocket, attempting to get at his insurance policy. The blond managed to elbow him in the ribs, but this only served to increase his determination. She managed to get her hands around the man’s neck, but it was too late; Number One deftly retrieved the twenty-ounce Mk 2 “pineapple” fragmentation grenade from his trousers and pulled the pin.

She dived through the compartment door and fell to the floor in the hallway. Afterward, the assassin known as Snow Queen thought that she remembered the flash of the explosion lighting the flat face of the American spy and the blast lifting his thick black hair so that it stood on end. The noise was a long time coming. Before she heard the explosion, like the snap of a heavy howitzer, she saw the whole body of the train car swell like a balloon full of water. The glass blew out and the compartment door cut through the rest of the car like a great black knife.

Concussion sent blood gushing out of her broken nose. She could hear nothing except a high ringing in her ears. All around her, mouths opened in noiseless screams of terror. She lay where she was with her eyes open.

In a few hours a policeman wearing a lacquered French helmet liner leaned over her and spoke. The blond woman pointed to her ears and said, “I’m deaf.” She heard nothing of her own voice but felt its movement over her tongue. The policeman pulled her to her feet and led her out of the debris. She would have been killed by the fire truck that roared up behind them if the Frenchman had not pulled her out of the way.’Is this coherent? I thought it was, and thoroughly enjoyed it: a close, terse, vividly painted fight, but also spinning off unexpectedly to a dream sequence, and ending with a superb piece of description of an explosion and its aftermath. I was hooked, and wanted to read on.

The scene is constructed entirely from three other passages, one by Raymond Benson and two by Charles McCarry. Here’s the scene by Benson, from Zero Minus Ten:

‘With a shout, he leapt in the air and delivered a Yobi-geri kick to Bond’s chest, knocking him back. The blow was meant to cause serious damage, but it landed too far to the left of the sternal vital point target. Michaels was momentarily surprised that Bond didn’t fall, but he immediately drove his fist into Bond’s abdomen. That was the assassin’s first mistake – mixing his fighting styles. He was using a mixture of karate, kung fu, and traditional Western boxing. Bond believed in using whatever worked, but he practiced hand-to-hand combat in the same way that he gambled. He picked a system and stuck with it.

By lunging at Bond’s stomach, the man had left himself wide open, enabling Bond to backhand him to the ground. Giving him no time to think, Bond sprang on top of him and punched him hard in the face, but Michaels used his strength to roll Bond over onto his back, and, thrusting his forearm into Bond’s neck, exerted tremendous pressure on 007′s larynx once again. With his other hand, the young man fumbled with Bond’s waterproof holster, attempting to get at the gun. Bond managed to elbow his assailant in the ribs, but this only served to increase his aggression. Bond got his hands around the man’s neck, but it was too late. Michaels deftly retrieved the Walther PPK 7.65mm from the holster and jumped to his feet.

“All right, freeze!” he shouted at Bond, standing over him, the gun aimed at his forehead…’Here is the passage from McCarry’s Second Sight:

‘Patchen kept hearing Maria Rothchild’s voice and smelling the smoke from her stinking Gauloises Bleues cigarettes, but he knew these sensations were only a dream. In reality he was floating in a sampan on the River of Perfumes, listening to a tinny phonograph record of a girl singing in Vietnamese. Vo Rau translated the lyrics: “She says that God is the smallest thing in the universe, so small that he cannot be imagined; he does not wish to be imagined, so he fills the sky with the stars that are his uncountable thoughts and we look not at the place where he is, but at the places where he has never been.” Patchen nodded sagaciously; this much of the truth he had already perceived. How beautifully the girl sang, how the river smelled of the flowers that turned its torpid waters into perfume, how much like his own mind and voice were the mind and voice of Vo Rau! It was uncanny.

Someone seized Patchen’s lower lip and twisted. The pain changed his idea of where he was. Maria Rothchild said, “Wake up, David.” His right eye focused, briefly, and he glimpsed Maria’s face.’And here’s the passage from McCarry’s The Tears of Autumn:

‘Afterward, he thought that he remembered the flash of the explosion lighting the flat face of the Chinese boy and the blast lifting the boy’s thick black hair so that it stood on end. The noise was a long time coming. Before he heard the explosion, like the slap of a heavy howitzer, he saw the whole body of the car swell like a balloon full of water. The glass blew out and one door cut through the crowd like a great black knife.

Concussion sent blood gushing out of his nose. He could hear nothing except a high ringing in his ears. All around him, mouths opened in noiseless screams of terror. He lay where he was with his eyes open.

In a few moments a policeman wearing a lacquered American helmet liner leaned over him and spoke. Christopher pointed to his ears and said, “I’m deaf.” He heard nothing of his own voice but felt its movement over his tongue. The policeman pulled him to his feet and led him toward the end of the street. He would have been killed by the fire truck that roared up behind them if the policeman had not pulled him out of the way.’Fairly astonishing. I think it is too easy to say with the benefit of hindsight that the joins are easy to spot in the scene above. I don’t think that is the case, even reading it again now. It is also well established that combining different pieces of one’s own writing can create fresh and surprising effects and resonances, and I think thrillers often thrive on this sort of dotting about and unpredictability. It can be highly effective, and I think it was in this scene and many others. So I think it would be dishonest to claim that this subterfuge should have been obvious to any editor, or reviewer, or, well, me: even if you had read all three novels, and I had only read one, I think it would be chance if you spotted it. It took a certain amount of intelligence and ingenuity to have pieced these passages together to make a coherent and readable scene, and moreover Rowan did this for the entire novel, using over a dozen sources for his unholy but also illegal coupling. But this example, I think, illustrates the technique he used for the book. Action and a dialogue from Bond novels and Ludlum novels are interspersed with poetic flourishes and descriptions from across McCarry’s work. Jonathan Chase’s entire backstory is also taken from McCarry’s Second Sight, and grounds the character in a surreal but convincing espionage reality.

It took some ingenuity, but that ingenuity is still very limited, and in my view doesn’t even begin to equate with the talent and work of those he plagiarized. I suspect I could, if I wanted, create a novel in this way. I couldn’t write the original passages, though – that is quite another order of ingenuity, and how long Rowan took to piece passages from books together to make it read convincingly doesn’t matter in the least: it was a Charles Highway-style robbery of several other writers’ ideas, and unfortunately I was not familar enough with his sources to perform a Dr Knowd on him: I’m fairly widely read in the genre, I think, but I haven’t read every spy novel ever published, don’t have a photographic memory, and quite simply wasn’t looking for this. And while I think the idea to do this was cunning, albeit totally unethical and absurdly unlikely to have remained undetected for long once it reached thousands of eyes, I don’t agree that it would have been easier to have written the novel from scratch. I’m pretty sure he couldn’t do that, which is why he cut and pasted the whole book. Clever forgery does not stand on a level with original creation, and having good taste in which spy novels to plagiarize isn’t much to laud, either.

Some have said that plagiarism, derivation and influence are on a sliding scale, and I agree. Some newspapers mistakenly reported that Rowan plagiarized Ian Fleming, but it’s a thought-provoking error, as part of the reason I enjoyed it was because in many parts it read like a pastiche of Fleming, only played straight – a kind of Bond novel in inverted commas. And in some ways, that is what the post-Fleming novels are, because they are indebted to the original creation and trying to find new takes on it while having fun with what we all associate with Fleming’s books and the films adapted from them. Outside a James Bond novel, a villainous organization meeting in a secret headquarters reads as Bond pastiche. It is also the case that Ian Fleming was taken to court for plagiarism, and settled, and that he sometimes refashioned premises and ideas from other writers, as I’ve written about. In You Only Live Twice, James Bond’s philosophy is quoted as ‘I shall not waste my days in trying to prolong them. I shall use my time.’ As John Pearson revealed in his 1966 biography of Fleming, this line was Jack London’s, and Fleming used it without attribution.

One can argue what is acceptable behaviour in such matters, but I think it is clear that Fleming is on the end of the scale marked ‘sometimes derivative’ while Assassin of Secrets is at the other end, marked ‘straightforward plagiarism’. It’s a fascinating and bizarre thing to have done, but please don’t make the mistake of thinking there was anything admirable in it. The honest publishing professionals who paid him and spent their time promoting him, creating artwork for him, arranging events for him and all the rest in good faith, and the talented writers whose work he so shamelessly stole, deserve more respect than to glorify his actions as some noble anti-establishment ruse, piece of performance art or any nonsense of that sort. Rather than seeking fault with his victims, it would be much more responsible to condemn Rowan’s fraud and theft.

http://www.thea

A Conspiracy of Hogs: The McRib as Arbitrage

One of McDonald’s most divisive products, the McRib, made its return last week. For three decades, the sandwich has come in and out of existence, popping up in certain regional markets for short promotions, then retreating underground to its porky lair—only to be revived once again for reasons never made entirely clear. Each time it rolls out nationwide, people must again consider this strange and elusive product, whose unique form sets it deep in the Uncanny Valley—and exactly why its existence is so fleeting.

One of McDonald’s most divisive products, the McRib, made its return last week. For three decades, the sandwich has come in and out of existence, popping up in certain regional markets for short promotions, then retreating underground to its porky lair—only to be revived once again for reasons never made entirely clear. Each time it rolls out nationwide, people must again consider this strange and elusive product, whose unique form sets it deep in the Uncanny Valley—and exactly why its existence is so fleeting.

The McRib was introduced in 1982—1981 according to some sources—and was created by McDonald’s former executive chef Rene Arend, the same man who invented the Chicken McNugget. Reconstituted, vaguely anatomically-shaped meat was something of a specialty for Arend, it seems. And though the sandwich is made of pork shoulder and/or reconstituted pork offal slurry, it is pressed into patties that only sort of resemble a seven-year-old’s rendering of what he had at Tony Roma’s with his granny last weekend.

These patties sit in warm tubs of barbecue sauce before an order comes up on those little screens that look nearly impossible to read, at which point it is placed on a six-inch sesame seed roll and topped with pickle chips and inexpertly chopped white onion. In addition to being the outfit's only long-running seasonal special and the only pork-centric non-breakfast item at maybe any American fast food chain, the McRib is also McDonald’s only oblong offering, which is curious, too—McDonald’s can make food into whatever shape it wants: squares, nuggets, flurries! Why bother creating the need for a new kind of bun?

The physical attributes of the sandwich only add to the visceral revulsion some have to the product—the same product that others will drive hundreds of miles to savor. But many people, myself included, believe that all these things—the actual presumably entirely organic matter that goes into making the McRib—are somewhat secondary to the McRib’s existence. This is where we enter the land of conjectures, conspiracy theories and dark, ribby murmurings. The McRib's unique aspects and impermanence, many of us believe, make it seem a likely candidate for being a sort of arbitrage strategy on McDonald's part. Calling a fast food sandwich an arbitrage strategy is perhaps a bit of a reach—but consider how massive the chain's market influence is, and it becomes a bit more reasonable.

Arbitrage is a risk-free way of making money by exploiting the difference between the price of a given good on two different markets—it’s the proverbial free lunch you were told doesn’t exist. In this equation, the undervalued good in question is hog meat, and McDonald’s exploits the value differential between pork’s cash price on the commodities market and in the Quick-Service Restaurant market. If you ignore the fact that this is, by definition, not arbitrage because the McRib is a value-added product, and that there is risk all over the place, this can lead to some interesting conclusions. (If you don’t want to do something so reckless, then stop here.)

The theory that the McRib’s elusiveness is a direct result of the vagaries of the cash price for hog meat in the States is simple: in this thinking, the product is only introduced when pork prices are low enough to ensure McDonald’s can turn a profit on the product. The theory is especially convincing given the McRib's status as the only non-breakfast fast food pork item: why wouldn't there be a pork sandwich in every chain, if it were profitable?

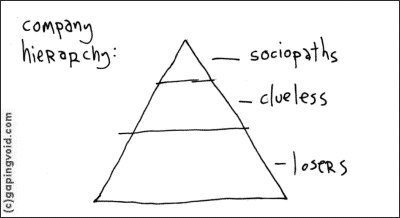

Fast food involves both hideously violent economies of scale and sad, sad end users who volunteer to be taken advantage of. What makes the McRib different from this everyday horror is that a) McDonald’s is huge to the point that it’s more useful to think of it as a company trading in commodities than it is to think of it as a chain of restaurants b) it is made of pork, which makes it a unique product in the QSR world and c) it is only available sometimes, but refuses to go away entirely.

If you can demonstrate that McDonald’s only introduces the sandwich when pork prices are lower than usual, then you’re but a couple logical steps from concluding that McDonald’s is essentially exploiting a market imbalance between what normal food producers are willing to pay for hog meat at certain times of the year, and what Americans are willing to pay for it once it is processed, molded into illogically anatomical shapes, and slathered in HFCS-rich BBQ sauce.

The McRib was, at least in part, born out of the brute force that McDonald’s is capable of exerting on commodities markets. According to this history of the sandwich, Chef Arend created the McRib because McDonald’s simply could not find enough chickens to turn into the McNuggets for which their franchises were clamoring. Chef Arend invented something so popular that his employer could not even find the raw materials to produce it, because it was so popular. “There wasn’t a system to supply enough chicken,” he told Maxim. Well, Chef Arend had recently been to the Carolinas, and was so inspired by the pulled pork barbecue in the Low Country that he decided to create a pork sandwich for McDonald’s to placate the frustrated franchisees.

But the McRib might not have existed were it not for McDonald’s stunning efficiency at turning animals into products you want to buy.

As McDonald's grows, its demand for commodities also grows ever more voracious. Last year, Time profiled McDonald’s current head chef, Daniel Coudreaut (I know what you’re thinking: two Frenchmen have been Executive Chef at McDonald’s? But no, Chef Coudreaut is American, while Chef Arend is a Luxembourger), whose crowning achievement so far has been turning a Big Mac into a burrito. In his test kitchen, we learn, a sign hangs that reads “It’s Not Real Until It’s Real in the Restaurants,” reminding chefs and cooks that their creations, no matter how tasty and portable they may be, must be scalable—above all else.

When the Time reporter visited the kitchen, Chef Coudreaut was cooking a dish that involved celery root—a fresh-tasting root that chefs love for making purees in the fall and winter. Chef Coudreaut proves to be quite a talented cook, but Time notes that “there is literally not enough celery root grown in the world for it to survive on the menu at McDonald’s—although the company could change that since its menu decisions quickly become global agricultural concerns.”

(Want to make enemies quickly? Tell this to the woman at the farmer’s market admiring the rainbow chard. Then remind her to blanch the stems a few minutes longer than the leaves—they’re quite tough!)

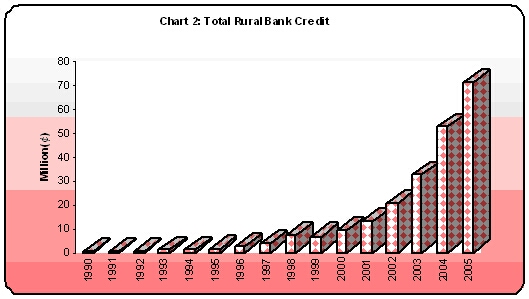

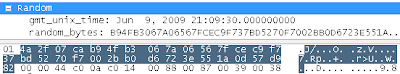

Now, take a look at this sloppy chart I’ve taken the liberty of making. The blue line is the price of hogs in America over the last decade, and the black lines represent approximate times when McDonald’s has reintroduced the McRib, nationwide or taken it on an almost-nationwide “Farewell Tour” (McD’s has been promising to get rid of the product for years now).

Key: 1. November 2005 Farewell Tour; 2. November 2006 Farewell Tour II; 3. Late October 2007 Farewell Tour III; 4. October 2008 Reintroduction; 5. November 2010 Reintroduction.

The chart does not include pork prices leading into the current reintroduction of the McRib, but it does show it on a steep downward trend from August to September. Prices for October, 2011 hogs have not been posted yet, but I suspect they will go lower than September—pork prices tend to peak in August, and decline through November. McDonalds, at least in recent years, has only introduced the sandwich right during this fall price decline (indeed, there is even a phenomenon called the Pork Cycle, which economists have used to explain the regular dips in the price of livestock, especially pigs. In fact, in a 1991 paper on the topic by Jean-Paul Chavas and Matthew Holt, the economists fret that “if a predictable price cycle exists, then producers responding in a countercyclical fashion could earn larger than ‘normal’ profits over time... because predictable price movements would... influence production decisions.” At the same time, they note that this behavior would eventually stabilize the price, wiping out the pork cycle in the process).

Looking further back into pork price history, we can see some interesting trends that corroborate with some McRib history. When McDonald’s first introduced the product, they kept it nationwide until 1985, citing poor sales numbers as the reason for removing it from the menu. Between 1982 and 1985 pork prices were significantly lower than prices in 1981 and 1986, when pork would reach highs of $17 per pound; during the product’s first run, pork prices were fluctuating between roughly $9 and $13 per pound—until they spiked around when McDonald’s got rid of it. Take a look at 30 years of pork prices here and see for yourself. Also note that sharp dip in 1994—McDonald’s reintroduced the sandwich that year, too. Though notably, they didn’t do so in 1998.

(I’m sure all the sharp little David Humes among us are now chomping at the bit—and you’re right to do so! This proves nothing. It is just correlation—and the sandwich doesn’t always appear when pork prices are low. In fact, the recent data could prove that McDonald’s actually drives pork prices artificially high in the summers before introducing the sandwich—look at 2009’s flat summer prices. Could that be, in part, because there was no McRib? On the other hand, food prices were flat across the board in 2009 so probably not. So, no, this correlation proves nothing, but it is noteworthy.)

Because we don’t know the buying patterns—some sources say McDonald's likely locked in their pork purchases in advance, while others say that McRib announcements can move lean hog futures up in price, which would suggest that buying continues for some time—and we can’t seem to agree on what the McRib is made of—some sources say pork shoulder, others say a slurry of offal—it’s hard to really make any real conclusions here.

The one thing we can say, knowing what we know about the scale of the business, is that McDonald’s would be wise to only introduce the sandwich (MSRP: $2.99) when the pork climate is favorable. With McDonald’s buying millions of pounds of the stuff, a 20 cent dip in the per pound price could make all the difference in the world. McDonald’s has to keep the price of the McRib somewhat constant because it is a product, not a sandwich, and McDonald’s is a supply chain, not a chain of restaurants. Unlike a normal restaurant (or even a small chain), which has flexibility with pricing and can respond to upticks in the price of commodities by passing these costs down to the consumer, McDonald’s has to offer the same exact product for roughly the same price all over the nation: their products must be both standardized and cheap.

Back in 2002, McDonald's was buying 1 billion pounds of beef a year. (As of last year, they were buying 800 million pounds for the U.S. alone.) A billion pounds of beef a year is 83.3 million pounds a month. If the price of beef is abnormally high or low by 10 cents a pound, that represents an $8.3 million swing (which McDonald’s likely hedges with futures contracts on something like beef, which they need year-round, so they can lock in a price, but this secondary market is subject to fluctuations too).

At this volume, and with the impermanence of the sandwich, it only makes sense for McDonald’s to treat the sandwich as a sort of arbitrage strategy: at both ends of the product pipeline, you have a good being traded at such large volume that we might as well forget that one end of the pipeline is hogs and corn and the other end is a sandwich. McDonald’s likely doesn’t think in these terms, and neither should you.

But when dealing with conspiracy theories, especially ones you aren’t quite qualified to prove, one must always consider other possibilities, if only to allow them to reinforce your nutty beliefs.

Counter Theory 1: An obvious reason that the McRib might be a fall-only product could be that people have barbecue (or at least things slathered in barbecue sauce) all the time over the summer—they would be less likely to settle for a cheap and intentionally grotesque substitute when they can have the real thing. Introduce it in the fall and you might catch that associative longing for the summer that HFCS-laden spicy sauces and rib-shaped things evoke.

To this I say: but what about winter?

Counter Theory 2: Another counter-theory comes from an online forum, where all good and totally reliable information comes from on the Internet. Here, an alleged graduate from Hamburger University claims that the McRib’s impermanence has nothing to do with pork prices, but rather that it’s a loss leader for McDonald’s—the excitement of a limited-time-only product gets people in the door, as we have noted, and they’ll probably buy the big drinks and fries with the Monopoly pieces on them because they’re, on average, impulsive and easy to fool.

To this I say: I knew that sandwich was a low margin product! All the more reason for McDonald’s to time it properly with price swings.

Counter Theory 3: The last, and most obvious, explanation is the official version of the story: the sandwich has a cult following, but it’s not that popular. Like "Star Trek," "Arrested Development" and that show about Jesus Christ returning to San Diego as a surfer, the McRib was short-lived because not enough people were interested in it, even though a small and vocal minority loved it dearly. And unlike these TV shows, which involve real actors and writers with careers to tend to, the McRib needs only hogs, pickles, onions and a vocal enough minority who demand the sandwich’s return, and will even promote it for free with websites, tweets and word-of-sauce-stained-mouth.

We’re marks, novelty-seeking marks, and McDonald’s knows it. Every conspiracy theorist only helps their bottom line. They know the sandwich’s elusiveness makes it interesting in a way that the rest of the fast food industry simply isn’t. It inspires brand engagement, even by those who do everything they can to not engage with the brand. I’m likely playing a part in a flowchart on a PowerPoint slide on McDonald’s Chief Digital Officer’s hard drive.

Ultimately what the McRib says about us as a society is perhaps worse than any conspiracy theory about pork prices. The McRib, born at the end of the Volcker Recession, a child of Reagan’s Morning in America, has been with us on and off over the last three decades of underregulated corporate growth, erosion of organized labor, the shift to an “ideas” economy and skyrocketing obesity rates. The McRib is made of all these things, too. When you think back to its humble origins, as both an homage to Carolina style pork barbecue, and as a way to satisfy McNugget-hungry franchises, it’s all there.

Barbecue, while not an American invention, holds a special place in American culinary tradition. Each barbecue region has its own style, its own cuts of meat, sauces, techniques, all of which achieve the same goal: turning tough, chewy cuts of meat into falling-off-the-bone tender, spicy and delicious meat, completely transformed by indirect heat and smoke. It’s hard work, too. Smoking a pork shoulder, for instance, requires two hours of smoking per pound—you can spend damn near 24 hours making the Carolina style pulled pork that the McRib almost sort of imitates.

And for its part, the McRib makes a mockery of this whole terribly labor-intensive system of barbecue, turning it into a capital-intensive one. The patty is assembled by machinery probably babysat by some lone sadsack, and it is shipped to distribution centers by black-beauty-addicted truckers, to be shipped again to franchises by different truckers, to be assembled at the point of sale by someone who McDonald’s corporate hopes can soon be replaced by a robot, and paid for using some form of electronic payment that will eventually render the cashier obsolete.

There is no skilled labor involved anywhere along the McRib’s Dickensian journey from hog to tray, and certainly no regional variety, except for the binary sort—Yes, the McRib is available/No, it is not—that McDonald’s uses to promote the product. And while it hasn’t replaced barbecue, it does make a mockery of it.

The fake rib bones, those porky railroad ties that give the McRib its name, are a big middle finger to American labor and ingenuity—and worse, they’re the logical result of all that hard work. They don’t need a pitmaster to make the meat tender, and they don’t need bones for the meat to fall off—they can make their tender meat slurry into the bones they didn’t need in the first place.

And unlike a Low Country barbecue shack, McDonalds has the means to circumvent—or disregard—supply and demand problems. Indeed, they behave much more like a risk-averse day trader, waiting to see a spread between an Exchange Traded Fund and its underlying assets—waiting for the ticker to offer up a quick risk-free dollar.

Witness to all this, Americans on both coasts tweet jokes about the sandwich, and reference that one episode of "The Simpsons," and trade horror stories, or play the contrarian card and claim to love it; and meanwhile, somewhere in Ohio, a 45-year-old laid-off factory worker drops a $5 bill on the counter at his local McDonald’s and asks a young person wearing a clip-on tie for the McRib meal, "to stay." The McRib is available nationwide until November 14th.

http://www.nyti

Old Subway Pros, Separating Drunk From Wallet

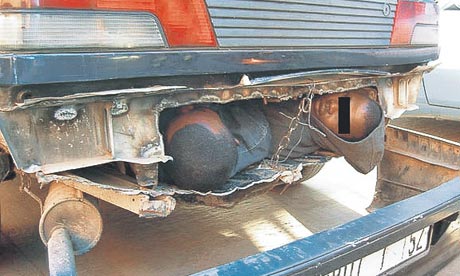

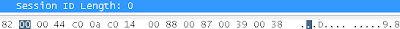

Part of the job for this officer, shown standing with a backpack, is looking for “lush workers.”

By MICHAEL WILSON

Published: November 4, 2011

In the world of crime statistics, there is a certain subsection of victim on the city subways: a reveler who, overserved during a night on the town, nods off on a train. He wakes with a flapping, precision-cut hole in his trousers and cool, thin air where his wallet used to be.

Related

This victim shakes his head in self-disgust, joining the besotted ranks to fall prey to a brand of criminal as old and established below the streets as a twisted root.

The police, long ago, coined a name for this criminal. The lush worker.

“Do they still exist?” said Lt. Kevin Callaghan, a 20-year veteran of the New York Police Department. “Yes.”

The lush worker sounds like a monster in a bedtime story, a stooped creature with a razor blade in one stealthy hand. Don’t drink, children, or the Lush Worker will get you.

But he is actually a middle-aged or older man who has been doing this for a very long time. And he is a fading breed.

“It’s like a lost art,” the lieutenant said. “It’s all old-school guys who cut the pocket. They die off.” And they do not seem to be replacing themselves, he said. “It’s like the TV repairman.”

Lush workers date back at least to the beginning of the last century, their ilk cited in newspaper crime stories like one in The New York Times in 1922, describing “one who picks the pockets of the intoxicated. He is the old ‘drunk roller’ under a new name.” While the term technically applies to anyone who steals from a drunken person, most police officers reserve it for a special kind of thief who uses straight-edge razors found in any hardware store.

The Police Department does not have a rough estimate of how many lush workers are out working lushes.

It offers an exact number: 109.

That is far fewer than there once were. What do we know of these 109 criminals? All but two are men, and overwhelmingly middle-aged or older, some born in 1947, 1943, 1938 and even, in one case, 1931.

They have all been arrested for lush working, or “lushing,” since 2006. They are persistent. One suspect arrested last weekend had 37 previous arrests under his belt — where, by the way, these guys like to hide razors, or in their hat brims or shoes or wallets.

And they are busy. “It happens every weekend,” said Officer James Rudolph with the police transit bureau that covers Manhattan below 34th Street, where many a young man goes to celebrate the weekend to excess.

“They’ll nudge them and see how incoherent they really are,” Officer Rudolph said. Then out comes the tool of the trade. “It’s unbelievable they don’t cut the person’s leg wide open. They’re like surgeons with a razor blade, for God’s sake.”

His commanding officer, Capt. Paul Rasa, said there had been 15 arrests of lush workers in that downtown district this year, and 35 complaints, which represent 28 percent of all the downtown transit grand larcenies in 2011.

This does not count unreported thefts. Victims, after all, are perhaps understandably ashamed to come forward to report being drunk enough to not have noticed the filleting of their pants by a man born in 1931.

“I had a guy take a swing at me once,” Lieutenant Callaghan said, recalling waking a construction worker with newly ventilated jeans. “He thought I robbed him.”

The victim of the theft on Sunday was 23 years old and referred to in a criminal complaint only as “a sleeping male.” The suspect, with 37 previous arrests, Robert Bookard, 48, is accused of cutting the man’s pocket and taking cash in a subway at the Brooklyn Bridge station at 3:40 a.m. A plainclothes officer saw the act and arrested him, finding three razor blades.

And yet, as Lieutenant Callaghan put it, “the cutting is a trade that’s going extinct.” Why? Pick a theory. Today’s subway robber is of the snatch-an-iWhatever-and-run variety that has recently driven up transit crime rates. With victims displaying $500 iPads in plain view, or passed out with a phone in their hand, why bother with a razor and a wallet?

Maybe the cutting is just too difficult. Officer Rudolph believes the good ones practice at home with mannequins.

And maybe the old thieves just don’t have anyone to teach.

The police keep track of who among the 109 is in jail, and when they are released. Lieutenant Callaghan sounds almost pleased to notice a familiar face on the train.

“I say, ‘Oh, you’re back,’ ” he said. “ ‘Good to see you.’ ”

http://www.thep

On Homesickness

November 2, 2011 | by Francesca Mari

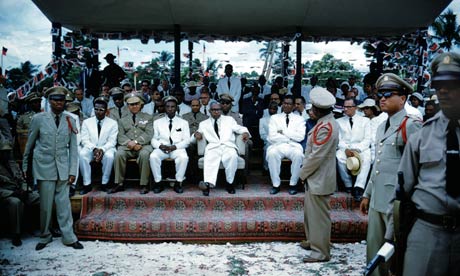

'The Soldier's Dream of Home,' a Currier & Ives lithograph produced during the Civil War, was one sign of the great attention that soldiers' homesickness received. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

A few weeks ago I found myself accidentally enacting the drama of a book I was reading. The book was Homesickness: An American History, and I was reading it on the subway, somewhat embarrassed by the title, which, held up right in front of my face, was like a sign saying: Here in New York, I can’t cut it. I comforted myself with the idea that I was only a few stops from home, where I could read safe from potential pity. But when I got to my door, I discovered that I’d locked myself out.

I looked up at my windows. I wished I could use the bathroom, foreign bathrooms costing at least a coffee. But it struck me that I didn’t long to be in my apartment. My place, with its card table in the kitchen and mattress on the floor, is unsettled—I would feel as dislocated inside of it as out. I can’t imagine what feeling settled here would look like; the only settled place I’m familiar with is the home where I grew up.

How long does it take to cultivate the feeling of home? I’ve been in New York for three years, on the East Coast for eight, and I’ve never suffered from acute homesickness. But still, when I’m called to define “home,” I think of El Granada, a town of 5,436 that staked itself twenty-six miles south of San Francisco down the coast. I mean staked quite literally: between 1906 and 1909, Ocean Shore Railway, which was building tracks from Santa Cruz to San Francisco along what is now Highway 1, planted thousands of fast-growing, blue gum eucalyptuses with the hopes of flipping El Granada into a seaside resort for train-traveling San Franciscans. The railroad company also commissioned the eminent architect and city planner Daniel Burnham (famous for the Flatiron building) to plan the streets. They go in two directions, up the hills and around them, so that it looks from above as if a four-square-mile spider web has been draped over the thousands of trees. But the dream of El Granada was not to be. Two years later the railway company collapsed. The tracks were abandoned. Some speculators bought land, but the place never really caught on until computers did in the late eighties and nineties, and intrepid commuters from Silicon Valley bought BMWs and began building houses.

I spent my youth resenting El Granada: it was not San Francisco, where I went to school and where my friends all got to go to sleep. When I go back now, I love looking over the Pacific, love the light streaming into the house from every exposure, but I am an American and so, as Susan Matt tells me, every cultural cue has lead me to deny that I might miss it. That’s the history of homesickness in America, one of increasing repression: homesickness wasn’t adaptive to a nation ever on the move to push out its borders, a place where wealth wasn’t inherited but found—so long as you were willing to look far enough.

The word homesickness didn’t come into use until the 1750s. Before that, the feeling was known as “nostalgia,” a medical condition. It was first identified in 1688 by Johannes Hofer, a Swiss scholar, who warned that the condition had not been sufficiently observed or described and could have dire consequences. By Hofer’s description, the nostalgic individual so exhausted himself thinking of home that he couldn’t attend to other ideas or bodily needs. While nostalgia was embraced as a Victorian virtue, a testament to civility and the domestic order, extreme onsets could kill a person. And so they did during the Civil War. By two years in, two thousand soldiers had been diagnosed with nostalgia, and in the year 1865, twenty-four white Union soldiers and sixteen black ones died from it. Meantime one hundred thousand Confederates deserted, presumably motivated by memories of mom’s hushpuppies. The war just about ended what little romanticization of homesickness had survived in the wilds of early America. A sentiment that caused desertion and death could no longer pass as a force for social good. Instead it had far greater utility as a patronizing justification of racism. Some in favor of slavery began to claim that slaves loved their home more than anyone; that being the case, how cruel to then tear them from the plantation.

An immigrant seeking a fortune couldn’t afford any semblance of I can’t cut it. Nor could a pioneer moving westward, or a Yankee trudging to California with a pan in his hand. WWI’s national training programs, the first of their kind, were designed to stifle homesickness from the start. Men from the same community were deliberately assigned to different units across America, so that they couldn’t retreat into the comfort of local remembrances. The aim was to turn each unit into a national entity whose first allegiance was to the country. In the 1950s, the age of the organization man, corporations attempted the same thing. Relocations were part of the path to promotion. IBM, employees joked, stood for I’ve Been Moved. After all, in a given year during the Eisenhower Administration, roughly twenty percent of Americans had.

But the institution most successful at destroying localism, at least today, is the American college. Places like NYU, Brown, Skidmore, and Harvard draw students from across the country, from around the globe, and in four formative years remagnetize the fresh new adults to the pole of the liberal arts university. No longer are their wants local; they’re national. Lifelong friendships and rivalries persist largely between classmates rather than childhood neighbors. If there’s one locality overwhelmingly represented at these liberal arts institutions, it’s New York, wherein so many of their graduates will subsequently settle.

New York is the colonial American experiment on speed, a holding pen for immigrants. Graduates—immigrants in sweatpants with big boxes of books—arrive every summer; they try to adjust and to profit; they either adapt or return home. In the 1920s and 1930s, parents prepared their children for such moves by sending them to frontier-themed summer camps where they would play pioneer. (Although camps today tend to be more hippie than hard-scrabble, their purpose may not be much different.) And where kids have camps to build resilience, college grads turn to New York as the ultimate test, not only of resilience but of that trait resilience is supposed to serve: ambition. Certain Manhattan hard-liners, the people who announce that “New York is the only city; though Paris is pretty,” think the only reason to leave New York is if you fail out.

A successful artist friend of mine recently decided to move back home to Boston after weathering New York for four years. He hated drawing, was tired of all the parties, and his gallery job, which was pleasant enough, would never give him a good salary. What he wanted was his home city, and a well-paying office job, where at 5 P.M. he’d be released to romp around with his young nephews. Among my friends his honesty was polarizing: some, like me, admired it; while many others felt threatened by his resignation from the rat race and what was perceived as a regressive retreat into familiarity.

But the problem with homesickness isn’t just that it impedes ambition; it’s that the object of longing, home, is not as fixed as one might think. After the Civil War, for instance, “the transcontinental railroad and steam-powered ocean liners,” Matt writes, “made it easier to return to a physical home and thus, at least theoretically, easier to assuage homesickness. Upon traveling back, however, they found they had not arrived, and never could, for the same technologies that had brought them home had also disrupted traditional ways of life.” The schedules and even the clocks of hometowns had been recalibrated to train schedules and standard time; certain commodities, like ice, reshaped the diet. Traveling back revealed that “home” had been vanquished by time, and a word necessarily arose to define this longing for what was lost: nostalgia.

While homesickness was suppressed in America, nostalgia was allowed to flourish. In 1899 New Hampshire figured out a way to profit off of it, and began throwing annual “Old Home Weeks.” These festivals, wherein the town might display old photographs and antiquated town artifacts while concessionaires in old-timey clothes served up regional specialties, were conceived of as reunions, meant to draw former residents back to their birthplaces. By 1903, these weeks were attracting half a million people, and today quite a few New England towns still throw them—such as Freedom, New Hampshire, which hosts one every August. Neither early El Granada nor my El Granada of the 1980s and 1990s had enough of a community to justify an antiquarian street fair. But America’s comparative acceptance—embrace, even—of nostalgia makes sense to me. It’s safer than homesickness because it’s neutered; it can’t be realized and won’t get in the way of work; it asks you to long only for something that no longer exists.

Which brings me back to my stoop on a sunny fall Saturday. I was out there for an hour, reading, before I finally decided to retrieve a key from my roommate near Penn Station. I caught the F train above ground, and the car elbowed around Gowanus before going under. My roommate handed me his keys outside the Pennsylvania Hotel, and I headed back to my apartment.

I thought about home home as I unlocked my door. In El Granada, my father had installed wireless and the eucalyptuses were being sawed down, while our neighbors’ nasty redwood hedges were growing taller and taller, strangling out ocean from our windows. Here, though, in my apartment, everything was static. My mattress was still on the floor, my card table still in the kitchen. The only thing that had changed was the light outside.

Francesca Mari has written for The New Republic, The New York Times Book Review, Bookforum, and other publications.

http://togopage

Le dramaturge camerounais Eric Essono Tsimi dresse un classement des meilleurs talents de la littérature africaine de ce début de XXIe siècle. Je reproduis ici l’article, publié sur SLATE.FR

Le dramaturge camerounais Eric Essono Tsimi dresse un classement des meilleurs talents de la littérature africaine de ce début de XXIe siècle. Je reproduis ici l’article, publié sur SLATE.FR

L’objectif, en établissant ce classement, n’est pas de remettre en cause la certitude que vous avez d’avoir rencontré votre meilleur auteur, lu votre meilleur livre, pour la première décennie du siècle. De gustibus et coloribus, non disputandum! Simplement, il peut être utile d’indiquer au lecteur qui ne consomme pas énormément de littérature quelles peuvent être les plus grandes réussites littéraires de l’heure, que ce soit des succès de librairie ou des succès d’estime. Seuls les auteurs s’étant épanouis durant cette décennie (2001-2010) sont considérés. La régularité dans la production est également un critère sur la base duquel je me suis déterminé, en prenant garde à ne pas me limiter aux écrivains de langue française. Enfin, tous les auteurs retenus dans ce classement ont publié au moins un roman ou un recueil de nouvelles et ont été récompensés par des prix prestigieux.

Qu’appelle-t-on écrivain africain?

Au-delà de la sélection forcément ardue, la difficulté réside surtout dans la définition de l’auteur africain que, entre double appartenance et schizonévrose identitaire, délimitent plusieurs frontières qui se superposent et s’anéantissent. La plupart des auteurs majeurs du continent, notamment au XXe siècle, étaient édités en France, en Grande-Bretagne, aux Etats-Unis d’Amérique… Hormis les auteurs sud-africains, il y a une ambiguïté qui frappe la production de la plupart de nos écrivains, qui sont souvent appelés «écrivain français d’origine camerounaise» (Mongo Béti) ou «écrivain français d’origine marocaine» (Tahar Ben Jelloun).

Au sens du présent classement, les écrivains africains sont ceux qui se réclament du continent, soit par leur thématique soit par leurs déclarations. La production littéraire africaine «intra muros» reste outrageusement débile (au sens premier de «faible») et imbécile (au sens étymologique de «sans force»), le Nigeria s’illustrant comme un cas exceptionnel, tant en quantité qu’en qualité. L’Afrique du Sud aussi, évidemment… Comme si la littérature était avant tout un privilège bourgeois qu’on pourrait corréler aux performances économiques!

Qui va, au terme du siècle courant, succéder à Naguib Mahfouz, Farah Nurrudin, JM Coetzee, Wole Soyinka, Mariama Bâ? Ces classiques des classiques, qui ont donné leurs lettres de noblesses, passez-moi la facilité du tour de phrase, aux littératures africaines. Qui sont ceux dont on parlera encore dans 90 ans?

Les 10 que je préfère

10. Leila Abouzeid

L’auteure marocaine de Last Chapter n’est sans doute pas l’écrivaine la plus prolifique et la plus inoubliable qui soit. J’ai eu un vrai coup de cœur pour son Année de l’éléphant. Leila Abouzeid n’est pas spécialement connue parce qu’elle est surtout traduite aux Etats-Unis, où elle a connu un beau succès d’estime.

9. Unity Dow

Le Botswana ne réussit pas uniquement au plan économique et social. Unity Dow, magistrate émérite, est aussi une écrivaine de talent. Sa thématique, dans les cinq romans qu’elle a écrits à ce jour, parcourt et recouvre les problèmes posés par la mondialisation dans nos sociétés africaines, le fléau du sida, ou la condition féminine. Elle a reçu plusieurs distinctions littéraires, aux Etats-Unis notamment. Son dernier roman, Saturday is for funeral, a été publié à Harvard Press. A lire absolument: Les cris de l’innocente.

8. Ex aequo: Ananda Devi et Kossi Efoui

L’une est Mauricienne, l’autre Togolais. Tout ce que Ananda Devi et Kossi Efoui ont en commun, en plus d’être Africains, c’est d’avoir été distingués par le Prix des cinq continents. Ils restent à mon sens des espoirs plus que des talents définitivement incontournables.

7. Léonora Miano

Son style n’est pas suffisamment osé, coloré, vivant, il exhale par moments les recettes d’écriture bien assimilées. Il n’empêche, Léonora Miano écrit d’excellents livres, avec sa plume qui rappelle Hamidou Kane ou le style par trop académique de son compatriote camerounais, l’excellent Gaston-Paul Effa. L’auteur des Aubes écarlates a fait, en quatre livres publiés en l’espace de cinq ans, une entrée en fanfare dans le cercle des très grands. Si cela perdure, si elle se diversifie et réussit à se réinventer dans ses prochains textes, elle est partie pour être à la littérature africaine ce que Samuel Eto’o est au football africain: un phénomène international. Ces âmes chagrines, publié chez Plon, est présenté comme un grand cru.

6. Yasmina Khadra

En France, son succès ne se dément pas depuis de nombreuses années, mais c’est depuis les années 2000 et son ralliement à Sarkozy que de nombreux Africains ont découvert l’œuvre de cet Algérien au pseudonyme si féminin. Yasmina Khadra est le seul dans ce classement à écrire des polars haletants qui n’envient rien aux maîtres américains du genre. Depuis 2001, chacun de ses romans a reçu une distinction littéraire majeure, Les Hirondelles de Kaboul, par exemple, a été primé en Algérie, au Koweït, élu meilleur livre de l’année 2008 par le San Francisco Chronicle.

5. Noviolet Bulawayo

La compatriote de Petina Gappah a reçu en juillet 2011, le Caine Prize for african writing qui est doté de près de 8 millions francs CFA (environ 12.000 euros) et d’un mois de résidence à l’université de Georgetown (Washington, Etats-Unis). Son Hitting Budapest est un chef-d’œuvre.

4. Zukiswa Wanner

L’œuvre de sa compatriote sud-africaine Zakes Mda me parle davantage, mais celle-ci a été accusée de plagiat à plusieurs reprises. Zukiswa Wanner, en revanche, est une écrivaine pleine de promesses qui sait dire l’Afrique du Sud post-apartheid. Avez-vous lu The Madams? Amour, sexe et bonheur garantis.

3. M.G. Vassanji

Ce Kényan de naissance, qui a grandi en Tanzanie, est davantage connu au Canada. Et c’est justement sur la chaude insistance d’amis canadiens que j’ai fait sa découverte. De M.G. Vassanji, je ne connais pour l’instant que sa Troublante Histoire de Vikram Lall (Giller Prize en 2004) qui m’avait été offerte. Mais en sus de tout le bien qu’on en dit, c’est suffisant pour le faire figurer dans notre liste.

2. Alain Mabanckou

Son dernier livre, publié chez Grasset, a été assez décevant; cela goûtait du réchauffé, il y manquait la folie, la variété et l’originalité de Bleu Blanc Rouge ou des Mémoires d’un Porc-épic. Alain Mabanckou reste pourtant l’un de nos plus fiers auteurs! Le Congo nous avait donné le plus beau poète francophone (Tchicaya U’tamsi), il nous avait révélé le dramaturge le plus puissant de sa génération (Sony Labou Tansi), il nous offre à présent le romancier le plus étincelant. Enseignant aux USA, ce grand promeneur a commencé son périple littéraire dans le très prestigieux L’Harmattan. Il a flirté avec le mythique Présence Africaine, a pris du galon chez Serpent à plumes, a été confirmé au Seuil et consacré chez Grasset, en raflant au passage bien des prix littéraires les plus courus en France et dans la Francophonie. Il est sans doute l’écrivain africain de langue française le plus traduit.

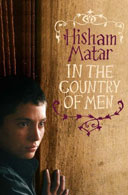

1. Chimamanda Adichie

Pourquoi elle plutôt que Helon Habila ou Segun Afolabi, tous Nigérians? Parce qu’il fallait choisir, et c’est à elle que va ma préférence. Il a suffi d’un livre qui ne m’avait jamais été recommandé, au sujet duquel je n’avais lu aucune critique, pour en tomber amoureux: L’Autre moitié du soleil. Dans son recueil de nouvelles Thing around your neck, Chimamanda Adichie réussit à entremêler traditions et cultures dans des histoires très actuelles. Outre cela, celle qui fut lauréate du Prix Orange (l’un des prix littéraires les plus prestigieux au Royaume uni, doté de 34.000 euros) en 2007 est fortement engagée dans les combats de son époque. Une intellectuelle comme on les aime, qui avait reçu en 2005, le Commonwealth writers prize pour son premier roman, L’Hibiscus pourpre. Si l’on considère enfin qu’elle est la benjamine (née en septembre 1977) qu’elle a eu un parcours universitaire impressionnant honoré «des plus grandes louanges» académiques, elle est sans doute l’écrivaine de sa génération qui domine le mieux notre époque.

Sortir de la complainte et de la négritude

Les écrivains africains actuels sont souvent inaudibles, pétrifiés dans leur zone de confort, confinés dans les classes où on les programme ou chez les spécialistes qui les étudie, atones dans nos propres médias, inexistants face aux intellectuels occidentaux. Et quand, comme Gaston Kelman qui, Dieu seul sait pourquoi, n’aime pas le manioc, ou Calixthe Beyala, l’«afrofrançaise», ils donnent de la voix, c’est de manière fort sélective qu’ils s’indignent, c’est surtout qu’ils ont cassé leur plume et ont cessé de nous épater par leurs créations. Les littératures africaines sont trop jeunes pour se satisfaire de ce qui a été fait au siècle dernier. Mongo Beti, par exemple, est le bâton de maréchal de la littérature camerounaise, une espèce d’autorité de principe, un écrivain lumineux qui surclasse, depuis 1958, tous les autres écrivains camerounais; il y a lui et en deçà il y a les autres, qu’un monde sépare.

L’écrivain africain n’est-il qu’un écrivain du désarroi et de la confrontation, qui peine à séduire son monde quand il ne se complait pas dans la complainte et ne parle pas de négritude, d’anthropophagie, de violence, de traumatismes, d’exotisme et de folklore? Pourquoi la modernité, le roman psychologique, l’amour, dans un contexte de croissance économique, de décadence du fait ethnique, d’alphabétisation à grande échelle et de conjuration de malédictions millénaires, dans cette face conquérante de l’Afrique, ne trouvent-ils pas preneurs (liseurs)? L’écrivain africain, aujourd’hui, est un écrivain qui se justifie, comme hier. C’est un écrivain qui écrit pour un public occidental auquel il destine sa prose que, sur place, ne lit et ne commente qu’une certaine élite urbaine.

Au total, l’écriture a été investie par les femmes, ce n’est pas un hasard si elles sont d’une si écrasante majorité dans notre classement. Messieurs, Allah n’est pas obligé d’être juste en toutes choses ici-bas!

Eric Essono Tsimi

Source: http://www.slateafrique.com/52233/classement-meilleurs-ecrivains-africains-du-debut-du-siecle

http://ask.meta

Poor (but pretty) in pastel

November 2, 2011 4:26 PM Subscribe

I worked at a legal aid office back in the day and remember seeing it among immigrants newly arrived from Asia, Eastern Europe, Africa -- but haven't seen it many years hence. I'm looking for pictures that show and/or any information about this bag.

posted by deadmessenger at 4:39 PM on November 2

posted by taramosalata at 4:42 PM on November 2

posted by elizardbits at 4:45 PM on November 2

This article calls them the refugee bags - and that in Ghana & West Africa they are called "Ghana Must Go" bags. In Trinidad they are "Guyanese Samsonite." In Turkey they are "Tuekenkoffer" or the Turkish suitcase.

posted by sestaaak at 4:47 PM on November 2 [1 favorite]

posted by jb at 5:01 PM on November 2

posted by skbw at 5:08 PM on November 2

posted by fresh bouquets every day at 5:14 PM on November 2 [1 favorite]

posted by thinkpiece at 5:24 PM on November 2

posted by vkxmai at 5:37 PM on November 2

posted by btfreek at 6:24 PM on November 2 [2 favorites]

posted by fatmouse at 7:28 PM on November 2

posted by taramosalata at 7:50 PM on November 2

You can see them in this shot.

posted by obiwanwasabi at 8:24 PM on November 2

posted by obiwanwasabi at 8:31 PM on November 2 [1 favorite]

That was exactly what I was thinking of and went GISing until I saw the "show one new" in this thread. Was nearly going to go through old Hong Kong films to try to find a screencap.

iirc, they were made from stuff much less advanced than tyvek; probably the same stuff that crinkly shopping bags are made from, but the weaving (on the scale of the individual colour panels, and the weaving of the colour panels) made them rather strong and resilient to abrasive damage. *Everyone* had them to carry groceries home from the "poor" markets in Hong Kong in the '80s/'90's. The "bring your own bag" movement, I guess, started a helluva lot earlier than in North America; there were definitely plastic bags when I went back to visit in '92 but it was nowhere near ubiquitous as in North America. If you got a bag, it was an expensive waxes/ceramicized paper bag with thick braided string handles and even metal grommets.

Hm, interesting to contrast the thriving sub-tropical forests of Hong Kong (seriously!) with the withered disposable plastic-bag-encrusted trees of Mexico of the '90s.

Still see a few carried by Asian garbage can pickers on campus at UBC; less, recently. I suspect that the bags that came with them started wearing out and they're switching to locally available sources for large durable cheap bags (mostly thick clear/clear-blue industrial trashbags that they "liberate" from the university).

posted by porpoise at 8:50 PM on November 2

posted by brujita at 11:27 PM on November 2

After the shop assistant found them, I asked her what they were called, for future reference. She thought for a moment and then said, "Bags".

posted by Georgina at 6:56 AM on November 3 [3 favorites]

Porpoise -- if you do decide to "go through old Hong Kong films to try to find a screencap," please post back with results!

posted by taramosalata at 11:21 AM on November 3

posted by skbw at 4:37 PM on November 5

posted by taramosalata at 5:37 PM on November 5

http://www.buck

Tributes to Anthony Williams

Published on Friday 9 February 2007 06:08

FRIENDS and family have left touching tributes to Anthony Williams, who was stabbed in Aylesbury during a fight in Cambridge Street in September 2006.

Since the devastating incident happened, friends and family have also been leaving floral tributes at the scene.

If you would like to add your tributes to this article, and this website, please click here.

-------------------------------------------------------------

Your comments so far...

Although i didnt know Anthony personally i know he was a really lovely young man. I would like to offer my heartfelt sympathy to Sharon, Lloyd and Luke and to all the Mould and Williams Families, my thoughts are with you at this very difficult time, from Richard MacCarthy.

-------------------------------------------------------------

To the willams family

Our thoughts are with you at this very sad time

Remember that your loss is shared

By many friends who care

And that you're in our

Thoughts and hearts

And in our every prayer

May you find courage

To face tomorrow

In the love that surrounds

You today

May the love of friends and family

Be a source of comfort to you all

At this time of sorrow

May these truths sustain you

Your loved one will always be

As close as a memory

And the god of all comfort

Is always as close as a prayer

God bless Anthony rest in peace

Till we all meet again

Mandy Mick & boys

xxx

-------------------------------------------------------------

blud u wer taken from us 2 soon man u had ur hole life ahead of u. u will alwayz b missed and never Forgotten fam

make sure u rest in piece and cheak on all friends from time-time. god bless

sj

-------------------------------------------------------------

R.I.P Anthony, we will always remember you. god bless x

Kara Moore & Grant Karwacinski

-------------------------------------------------------------

Anthony

I'M FREE

Don't grieve for me, for now I'm free

I'm following paths that were made for me,

I took a hand, I heard a call….

Then turned, and bid farewell to all.

I could not stay another day

To laugh , to love, to sing to play,

Tasks left undone that must stay that way,

I found my peace…at close of day

And if my parting left a void,

Then fill it with a remembered joy,

A friendship shared, a laugh a kiss,

Ah yes these things I too will miss.

Be not burdened…deep with sorrow

I wish you sunshine of tomorrow,

My lifes been full… I've savoured much,

Good friends good times, my family's loving touch

Perhaps my time seemed all too brief,

Don't lengthen it now with undue grief,

Lift up your hearts and share with me,

I,m wanted now …my soul is free.

With love from

Auntie Dianne xxx

-------------------------------------------------------------

THE MOULD FAMILY of JAMES TOWN ACCRA

Chief Kojo Ababio IV, of James Town

Chief Kobina Ghartey VII of the Royal House Winneba

Chief Herman Mould head of Mould family,

Grand father Desmond Mould and Grand Mother Jessie Mould Vanderpuije, Addy, Welbeck, Tagoe, Sackey, Quartey ,Bruce, Lutterodt and

Allied families

Regret to announce the Tragic Death of Anthony Williams

son of Lloyd Williams and Sharon Mould

Uncles :

William Mould, Allan Mould , Kem Mould ,

Aunties :

Ann Mould , Jessica Mould , Phoebe Mould and Irene Korsa

Cousins :

The Okwesa brothers, Ike, Chucks,Emeka, and Chuma

Tracey and Adza Mould , Fiona Wood and Grenia Forsom,

Ian Greenstreet ,Ivor Greenstreet Barrister at law

Ken Bismarck, Koranteng Ofosu Amaah, Andrew, Michael and Richard Nartey Dr Sophia Ofosu Amaah ,Dr. Bernice Ofosu Amaah Dr Yvonne Mensah

Great Uncles :

T.A. Tagoe, barrister at Law , Ray Tagoe ,Clarence Tagoe barrister at Law Joe Quartey Pappafio, Herman Mould, Victor Mould , Dr.William Mould Sonny Mould ,Alex Mould and Jacob Mould , Francis Mould, E .Oko Allotey, E . Ate Allotey , Professor S. Ofosu Amaah former Director of Public

Health University of Ghana and W.H.O New Yok.

Professor. G .K. A Ofosu Amaah former Dean faculty of Law , University of

Ghana.

V .Ate Ofosu Amaah former Director Ghana Commercial Bank

Mr W. Ofosu Amaah chief Counsel Legal Dept.World Bank, Washington,U.S.A. James Brown , George Mould, William Mould ,in U.S.A

Thomas Mould, John Mould in U.S.A., Thomas Sawyer , Bella Sawyer and Ade

Sawyer,

Ray Sowah, Irwin Sowah

Ben Mensah, Sackitey Crabbe , Nii Crabbe, Winston Asante Barrister at Law . Fifi Asante, Mr Afla Sackey , Ampim Sackey,

Great Aunties :

Mrs Emily Afful, Mrs. Gladys Hansen Quartey Mould ,Madame Mary Mould ,

Diana Okwesa, Mrs. Vicky Mould

Mrs Frances Sam ,

Prof..Miranda Greenstreet Executive Director of African Assoc.for Health

Enviroment and Development.

Mrs Betty Mould Iddrissu, Barrister at Law , Mrs Maud Blankson Mills, Mary Chinnery Hesse, former Deputy Director General ,Internation.Labour

Organisation. Geneva ,

Mary Elizabeth Mould, Brew Mould, Doris Brown ,

Delia Davidson, Mrs . Joyce Mould Owusu, Constance Sowah , Mrs. Annabelle Bannerman ,Barrister at Law, Honora Twumasi,

http://www.3qua

(Un)occupy Oakland: An Open Source Love Poem

I.

They have come for the city I love

city of taco trucks, wetlands reclaimed

water fowl with attitude, gutted

neighborhoods, city of toxic

waste dumps and the oldest wildlife refuge

in North America.

City owned by spirits

of Ohlone, home

to the international treaty

council, inter-tribal friendship house

City

in which I love and work, make art,

dance, share food, cycle dark streets at 2am

wind in my face, ecstasy

pumping my pedals.

City where women make family

with women

men with men

picnic in parks with their children

walk strollers through streets.

City that birthed the Black Panthers

who took on the state

with the deadliest of arsenals:

free breakfast for children, free clinics,

grocery giveaways, shoemaking

senior transport, bussing to prisons

legal aid.

City where homicide rate for black men

rivals that of US soldiers in combat.

City where I have walked precincts

rung doorbells, learned that real

democracy

is street by street, house by house

get the money out and

get the people in.

City of struggling libraries

50-year old indie bookshops

temples to Oshun, Kali-Ma, Kwan Yin.

City where Marx, Boal,

Bhaktin, Freire are taught

next to tattoo shops

bike collectives rub shoulders

with sex shops, marijuana

dispensaries snuggle banks

City of pho, kimchee, platanos, nopales

of injera, tom kha gai, braised goat,

nabeyaki udon, houmous and chaat,