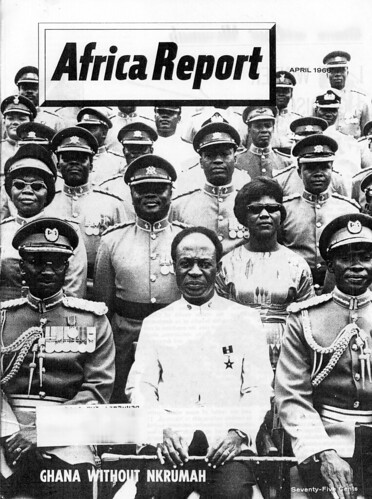

Ghana without Nkrumah

The Winter Of Discontent

Irving Markovitz

Africa Report, April 1966

Some observers have been surprised by the apparent unanimity of support

in Ghana for the little-known army officers who led the coup d'etat

against President Kwame Nkrumah on February 24. Their astonishment

paralleled the embarrassment of the Chinese chief of protocol who had

to seat the deposed leader at a state banquet in Peking even as the

Ghanaian Embassy was removing Nkrumah's portrait from a sidewalk

display case in the Chinese capital. In Accra itself, members of

Nkrumah's personal guard regiment mounted an armed resistance to the

takeover, but it was all over in a few hours. The old regime died

quickly, and with it the nine-year rule of West Africa's original and

seemingly best established nationalist leader. From an overseas

viewpoint, it has been hard to reconcile the coup with the fact that a

consensus on government and policy had seemed to emerge in Ghana out of

the struggle between originally antagonistic interests. Unlike many

other African countries, including several that have recently

experienced military takeovers, Ghana seemed to have passed

successfully through its time of troubles. Some regimes are unstable

because important elements are neither represented in them nor

decisively suppressed; but in Ghana, in one way or another every major

social group had apparently reached an understanding with the regime.

Politics was not the monopoly of an elite coalition of middle-class

intellectuals and a traditional hierarchy that excluded the peasants,

skilled laborers, and businessmen. There was considerable unrest and

dissatisfaction, several assassination attempts against Nkrumah, and

constant rumors of coups, yet the government had made conciliatory

gestures toward its opponents both within and outside its ranks, and

showed every sign of having attained a durable balance of interests.

Perhaps the kindest verdict on Nkrumah in the Western press was that he

tried too hard and was in too much of a hurry. He was called a "clown"

in the London Observer, and "Stalin-like" in the New York Herald

Tribune', The New York Times made his 1961 proclamation of compulsory

education appear to have been a totalitarian act. Yet, to interpret

Nkrumah as a ruthless totalitarian leader -a kind of sub-Saharan

Hitler-is to misunderstand both the sources and the loss of his power.

Seeds of Change

Ghana was neither a terrorized nor a poverty-stricken country. In

traveling overland to Accra from francophone Africa, for example, two

things were striking: the visible wealth of Ghana, and the visible

breadth of its distribution. The number of cars, the condition of

residential areas, roads, restaurants, shops, markets, office

buildings, and department stores-and the widespread use of these

facilities by Africans, not just the European commercial and technical

elites- produced the image of a far from destitute country. Beneath the

surface there were chronic periodic shortages of many imported goods,

including basic foodstuffs, and mounting inflation.

Civil liberties were in a chaotic condition marked by the dismissal of

judges and the retrial of cases which resulted in verdicts unfavorable

to Nkrumah. The abuses of preventive detention and the outlawing of

opposition parties were notorious. To assert, however, that the mass of

the people lived in terror would be quite wrong. The commonly accepted

estimate of the number of Nkrumah's political prisoners is 1,100, and

reports of individual beatings by prison guards may well be believed.

On the other hand, credible evidence of systematic torture has yet to

be produced, and though the old regime sentenced several people to

death for participating in one of the assassination plots, no one in

Ghana appears to have been executed for a political crime.

In these circumstances, a mass revolt against tyranny or impoverishment

was unlikely, and to suggest that the Army intervened only when the

government had begun to lose control of the "forces of discontent"

explains little. Every African country harbors similar discontents

arising from unemployment, low wages, and economic and social

disparities. The Army is said to have chafed at Nkrumah's non-military

decision to ask the USSR to train and equip one part of its forces, and

Britain and the Commonwealth the other part. Another irritant was

Nkrumah's proposal to create a "People's Militia" that would be

separate from the Army, and hence a potential threat to the Army's

authority and its share of the annual budget. Colonel E. K. Kotoka,

commander of the second army brigade at Kumasi and leader of the coup,

announced on the day of the takeover that the Army was motivated by

Ghana's serious economic and political situation. It was unthinkable,

he said on Radio Accra, that Ghana's economy had developed in the last

three years at a rate of only three percent per annum, given its vast

potentialities. He accused Nkrumah of running Ghana as his personal

property and bringing the country to the "brink of bankruptcy." He

promised a sweeping revision of economic, financial, and political

affairs that would include a constitutional referendum on a new system

of government based on the separation of powers, and a reversal of

Ghana's mounting economic dependence on the Communist world.

The military regime quickly announced that it would redirect trade

toward the West, make no new barter agreements, curtail Communist aid,

reverse Nkrumah's, long march toward "scientific socialism," outlaw the

ruling Convention People's Party (CPP) and all other political

activities, and eventually return Ghana to civilian rule. The Soviet,

East German, and Chinese technicians were asked to leave. At the Army's

request, senior civil servants took charge of all ministries and the

provincial administrations, and eight of them issued a statement in

support of the new regime.

Taming the Opposition

The Army's seizure of power was the climax of a long sequence of

changes in Ghana's society and governmental system. Ghana has undergone

a very rapid evolution in which the Convention People's Party, which

brought the country to independence in 1957, continued to govern in the

post-independence period, while successfully overcoming opposition from

distinctly different sources. Before Ghana became self-governing, the

issues were the pace of advance to independence, and who would control

the government at this critical transition point; deep conflicts arose

over the purpose and nature of every significant governmental

institution.

As far back as 1954, the particularistic National Liberation Movement

in Ashanti and the cocoa growers had found common cause in opposing the

growing influence of the "coastal modernizers' The Ashanti-cocoa grower

nucleus attracted other interest groups, among them the Togoland

Congress and the Northern People's Party. The British-sponsored

constitutional instrument drafted just prior to independence in 1957

sought to accommodate these forces in a semi-federal system, but the

post-independence government did not wait long to adopt a hard line

toward them. It repealed the constitutional provisions that encouraged

regionalism, passed legislation against regional and tribal political

parties, and compelled the opposition forces to recombine in a national

organization which in fact incorporated regionalism under a different

name.

After 1957, the only opposition group with a significant mass following

was the United Party, a coalition of disparate ethnic and religious

interests joined principally by their resistance to the unifying

policies of the CPP. This original anti-Nkrumah group was founded with

the blessing of the Asantehene, traditional leader of the Ashanti, soon

after the passage in 1954 of legislation reducing the government price

for cocoa and thus increasing the amount of money available for

government development schemes. The names of the five groups that

composed the United Party are indicative of the interests involved: the

National Liberation Movement (itself a coalition of anti-CPP

interests), the Northern People's Party, the Moslem Association Party,

the Togoland Congress Party, and the Ga Shifimo Kpee. The old

middle-class intellectuals-the doctors and lawyers who had advised the

colonial administration and were the first moderate reformers-were also

opposed to the CPP's policies of socialization, and still resentful of

having been pushed aside by the more vigorous young nationalists.

Combined, these forces were a powerful movement for the redress of

individual grievances, and the strong traditional loyalties attaching

to the Asantehene, plus the organizational and theoretical ability of

the intellectuals, enabled the party to attract a mass following.

None of the groups embraced in the United Party thought primarily in

terms of national unity or orderly economic development based on a mass

mobilization of the people. The cocoa farmers were unwilling to

postpone immediate consumption for enforced savings; at most, they held

that funds not paid directly to them should be invested in their local

area, and not spread thinly over the country to be used to the

advantage of "foreigners." Tribal leaders, who at one time were willing

to hand over the government to freely elected representatives and admit

that they had no place in party politics, were encouraged by their

alliance with the cocoa farmers to revive their aspirations to a share

of power. The opposition platform advocated a complex system of

federation in which regional governments were to assume most of the

powers of the central government. Traditional leaders were not only to

head each region, but were also to dominate the cabinet and the upper

house of a bicameral parliament. Most significantly, these officials

would not be elected, but would rule by virtue of their ancient

positions; only the lower house was to be chosen by universal suffrage.

Revenue for the federal government was to be derived from limited

sources, and a broad-based tax prohibited.

Nothing could have been more irritating to the CPP. Federation would

strengthen tribalism and virtually stifle economic development, and

Nkrumah accordingly considered the United Party's proposals a

fundamental challenge to the system of government. Western standards of

secular government, he believed, could not accommodate the divisive

loyalties commanded by "uneducated and parochial minded" tribal

leaders. Loyalty to the Asantehene meant focusing on the past and

Ashanti, instead of looking to the future and the nation. Chieftancy

might be exalted as a monument to Ghana's proud African heritage, but

it could not be allowed to play an active role in contemporary politics.

At stake were opposing philosophies of government. In view of the

latter-day cynicism of the Nkrumah regime, it may well be difficult to

recall the moral fervor of the time. Followers of the CPP were

convinced that they were fighting not for selfish interests, but for

the creation of a national society. Because they could not agree on

basic ends, the antagonists sought victory through intense conflict

rather than compromise; and because the CPP saw the traditional

interests (which would grow fat on cocoa surpluses while others went

hungry) as a national menace, it believed that harsh repression was

morally justified and socially necessary.

Among the first people thrown into jail under the Preventive Detention

Law were wealthy Ashanti cocoa farmers, anti-government intellectuals,

and tribal leaders who wished to subordinate the disciplines of

economic development to the interests of a weak federation based on an

indirect electoral system that would favor the traditionalists. This

original opposition challenged the authority of the government, and the

structure and polity of the state itself.

To cope with an opposition that threatened the unity of the state and

widespread public disorder that included assassinations and bombings,

the government resorted to a series of repressive measures,

deportations, arrests, censorship, and overt intimidation. For the most

part, these acts were directed at limited political objectives, and in

the circumstances some of the measures were obviously needed. Moreover,

for an understanding of the recent coup d'etat, it is important to note

that the government's actions were not altogether arbitrary, but were

sanctioned by law. Each of the legal measures was approved by a

popularly elected parliament and was accepted by the elements in the

governing groups, as well as by many of the bureaucrats and

technicians. Increasingly, however, the government enacted capricious

and arbitrary laws marking a sharp departure from the standards of

rationality established by the British Colonial Service, and from the

standards of the revolution itself.

At the same time, the government was installing the machinery of

coercion. It obtained an increasing number of anti-riot vehicles and

other quasi-military hardware, enlarged the police force, established a

reserve army, and organized a secret service. Again, given the

circumstances, these measures seemed not unreasonable. The net result,

however, was the strengthening of an institution - the Army - that

proved lethal to the regime that nurtured it. This history

differentiates the Army of Ghana from the armed forces of most other

African states, and provides the context for the coup d'etat.

As the clash of political objectives drove the CPP to greater militancy

against the United Party, the opposition in turn was compelled to

reassess and eventually modify its position. It dropped the issue of

federation and began for the first time to place a high value on

parliamentary institutions within a unified Ghana as a forum for the

expression of its demands. Chiefs abandoned their interference in

secular life. Economic development was universally accepted as the

major objective of all social groups. Where once Nkrumah stood almost

alone in arguing that "progress could be measured by the number of

children in school, the quality of their education, the availability of

water and electricity, and the control of sickness," these goals became

the aspiration of the whole society. Long before the end of the regime,

large numbers of traditional notables had joined the CPP, taken their

seats in many councils, and proved themselves flexible enough lo become

influential and persuasive spokesmen. The drawing of new boundaries lo

the political arena was perhaps Nkrumah's major accomplishment.

Cracks in the Consensus

In September 1961, hundreds of workers went on strike, and a

qualitatively different kind of opposition began to arise in the ranks

of organized labor. Originating among the harbor and railway workers in

Takoradi, the walkouts spread to the industrial and commercial workers

in Sekondi and Kumasi. Municipal transport employees in Accra soon

joined the movement, and workers staged brief sympathy strikes

throughout western Ghana. The walkouts were essentially a protest

against government austerity measures that reduced the average worker's

buying power by raising the cost of basic imports dramatically, almost

overnight. Clothing and shoes rose by a third, and food prices soared

as transportation costs increased. To forestall inflation, the

government lightened existing controls on wages, and imposed a

compulsory savings scheme by which five percent was deducted from all

wages and salaries in excess of £120 a year, and invested in

interest-bearing development bonds.

The strikers ignored back-to-work appeals from their union leaders as

well as from the government, which came under heavy fire not only from

the formal opposition but also from loyal CPP supporters who ordinarily

looked to Nkrumah for leadership. The strike thus marked the beginning

of a different type of opposition from within the government's own

ranks. It touched the heart of its mass support in the coastal cities

where the strikers had earlier endorsed the government and its policies

by large majorities. This new opposition sought some compromises and

modifications of the program for reaching the goals they had already

agreed on, though they did not challenge the goals themselves.

When the government imprisoned the leaders of the strike, thus adding a

new category of prisoners held under the Preventive Detention laws, the

CPP appeared to be on the threshold of a, period of violence and terror

in which The government turned against its own| mass base and

suppressed The very people who had brought it to power. In an earlier

day this possibility would have been academic, for the government did

not command sufficient instruments of repression to dismember the old,

semi-feudal opposition by force. By 1961 however, the coercive

apparatus of the state had increased enormously in strength, and there

was a wing within the ruling party that urged its use.

A showdown was avoided as the government retreated from the system of

compulsory savings, and a return to normality seemed to follow. Behind

the facade, however, the strikers had revealed not only a growing

discontent with the government's austerity measures (which had indeed

been anticipated), but also the extent lo which the trade union leaders

were acting as tools for the CPP and the state.

Meanwhile, the influence of the CPP's militant wing was shown in

attempts to intensify the ideological indoctrination of the people

and the key elites. Several new doctrinaire journals were

established; the Kwame Nkrumah Ideological Institute was opened at

Winneba, and an effort was made lo reorient the university along

ideological lines. Soviet, Chinese, arid East German technicians began

to arrive in increasing numbers; trade with the Eastern bloc was

increased, sometimes under disadvantageous conditions; attacks against

United States policies became increasingly vituperative, and the

ideological theme shifted from an emphasis of the uniqueness of the

African personality to the universal applicability of scientific

socialism. Most important of all, economic decisions apparently came to

be made primarily on the basis of ideological factors rather than

economic Calculations. The expenditure of millions on a convention hall

or an Olympic sports center, and the decisions to continue losing money

on an airline or unprofitable factories, or in disadvantageous barter

deals with the USSR, were justified in terms of a certain political

calculus. These apparently self-defeating choices can be viewed as

highly rational in the perspective of men who believed strongly in

building African unity and scientific socialism in a short time.

Granting that millions were spent on prestige projects, the key

question remains unanswered: what percentage of the government's total

expenditure did these projects represent? The assertion that Nkrumah

brought Ghana to the verge of bankruptcy does not take into sufficient

account the catastrophic drop in the price of cocoa on the world

market, and ignores long-range, highly productive projects, such as the

Volta development scheme, which are coming to fruition years ahead of

schedule, but which had until now been a drain on the economy. It turns

a blind eye to what Ghana got for its money: an extended life

expectancy from fundamental improvements in medical services,

nutrition, and hygiene; a huge educational system serving a larger

percentage of school age children than in any other Black African

country; the creation of thousands of jobs; and an economy at the

threshold of self-sustaining development.

Nkrumah and the militants of the CPP would argue that these

accomplishments were achieved not despite, but because of, political

persuasion and manipulation and an ideology to guide the selection of

objectives and strategies. To them, independence from the British,

unity within the state, and financing for the Volta project were

equally political objects. They believed that without a sound

"ideological" and "political" foundation, Ghana could not hope to

prosper.

Alienation of Peasants and Bureaucrats

It is well known that the ideological militancy of the regime was

accompanied by corruption. The effects of corruption were felt deep in

the bush, where the peasantry accepted Nkrumah's overthrow for reasons

far removed from the policy questions that seem to have motivated the

military. People in the bush know whether a regime is corrupt. The

peasant is rightly suspicious, for there is always some doubt as to the

social consequences of any innovation. After he has spent six to nine

months hoeing, sowing, weeding, and harvesting a crop of maize, cocoa,

cotton, or peanuts, what must he feel-a man who has never been lo town

-as he holds for the first time a few banknotes in his hand and watches

the truck with his stuffed sacks trundle down the road-to where?

Ultimately, corruption in an underdeveloped country operates to milk

the peasant. The salaries of functionaries and politicians, who arc the

best organized interests in the society, tend to be downwardly

inflexible, but peasants, to the extent that they are engaged in a

market economy, have a minimum of economic resources and organizational

skills, and are highly vulnerable to economic exploitation. Corruption

poisons the atmosphere; the government loses authority as enclaves of

power are established in urban areas where a small. Westernized elite

holds a monopoly of influence. In such a situation, the peasants always

oppose the regime - or more precisely, they are increasingly separated

from it. To avoid unnecessarily alienating the peasantry is one of the

principal reasons that Communist regimes are notorious for their

puritanism.

Whether corruption is equivalent to waste depends on the type of social

system in which it occurs, for it may serve functionally to keep

certain elites and classes satisfied. If assuaging such interests is a

necessary consideration, then corruption may be the least painful

(because it is the most indirect) method of achieving stability. From

the perspective of economic development, however, corruption

perpetuates stagnation by cur tailing capital, and robs the government

of its political persuasiveness and moral authority. The technical

knowledge necessary for the introduction of scientific agriculture is a

monopoly of the educated government intelligentsia. To educate the

peasant involves convincing the peasant to listen and to do a great

many things that seem unnatural and threatening. Leadership of this

kind is possible only when there is moral authority, not simply force,

and this is true no matter how knowledgeable the technician.

As corruption was alienating the peasants in Ghana, it was also

arousing resentment among the civil servants and technicians who worked

with the peasants in the back country. Their task of inducing the

peasantry to accept modern agricultural techniques became increasingly

difficult in proportion to the government's loss of credibility among

the rural masses. The alienation of both groups in turn affected what

the French call encadrement - that is, the reorganization of the

populace into a social structure that makes the resources of the

community available for economic development. Encadrement was not only

the next logical step following the government's defeat of semi-feudal

rural interests; it was also essential if unfulfilled material

ambitions - the so-called revolution of rising expectations-were to be

satisfied in the country at large.

The unsolved problem of restructuring the rural society was a basic

issue underlying Nkrumah's ouster. On the one hand, the government

could choose among a variety of ideological solutions ranging through

Chinese communalization to Moshavism or laissez-faire capitalism. On

the other hand, the problem could be viewed simply as a technical

exercise in maximizing output. Militants within the ruling party, the

press, radio, youth organizations, and trade unions pressed for an

ideological solution. Opposing them were the "technocrats," who

included members of the higher civil service.

Two things distinguished the technocrats from the nucleus of civil

servants carried over from pre-independence days. First, their large

numbers: the government acquired thousands of employees as it

Africanized the administrative structure, extended its services from

the large cities to millions of people in the bush, and undertook

sweeping programs of welfare and economic development, instead of

confining itself (as did the colonial administration) to the household

tasks of maintaining peace, order, and a system of justice.

A second distinction is their awareness of membership in a technocratic

elite. From the apolitical British tradition, in which neutrality is a

source of pride and effectiveness is conceived as a concomitant of

non-involvement, the newcomers to Ghana's bureaucracy slowly developed

an awareness of a collective interest distinct from the interests of

the politicians, who, in the British tradition, were entitled to make

policy. By their style of dress, patterns of speech, education,

training, vocabulary - and by the images in their heads, their

attitudes toward economic development, political goals, and methods of

governing - the administrative elite can be distinguished from the

political elite. They found Nkrumah's personality cult objectionable,

and the servile flattery bestowed on him in many quarters demoralizing,

because it clashed with the tastes and traditions of the civil servant.

This is not to say that the technocratic elite, a bulwark of the new

military government, is democratic. The men most deeply concerned with

economic development have a manipulative attitude toward the rural

groups with whom they work. They make no hortatory appeals to the

crowd-a major distinction between the technocrats and the ousted

politicians. Their approach is that of the social worker to his

culturally and educationally deprived brethren. They appeal to the

villagers' "home-town spirit" and "reason" with them until they accept

previously decided projects, then reward the village with a ceremony

attended by the local notables and honored by greetings from national

officials. In going about their work, the civil servants make little

effort to identify with the villagers; rather, they attempt to persuade

the villagers that they, as technicians, can be of use by virtue of

their unique knowledge and skills. Nor, in Nkrumah's day, did they make

an effort to identify themselves to the people as party members. They

often cooperated with the party, particularly in local community

development projects, and some indeed were card-carrying members of the

CPP. But when they joined the party, they did so because membership was

useful to their careers, not out of political conviction.

These functionaries are little interested in ideology or

indoctrination. They brush aside questions on socialism or the African

personality, preferring to discuss their programs in terms of specific

goals and rational techniques to meet them. They judge their

accomplishments objectively and honestly, and readily admit mistakes.

In sum, their efforts are directed toward the creation of a social

system based on rational calculations demanding predictability and

regularity in the conduct of affairs. By their attitudes, training, and

objectives, they consider themselves a class apart from the politicians

as well as from the people-a purposeful class that knows how to get a

job done, if left alone to do it. Perhaps their biggest complaint was

that Nkrumah's government did not always consider their work important

enough. Their budget requests were often cut, their resources limited,

and their advice rejected; worst of all, the government made decisions

on the basis of criteria they could not accept, on the counsel of

ideologues they could not tolerate.

The Army Holds the Bag

Ghana's real problem on the eve of the coup was deeper than the threat

of bankruptcy, for national productivity was still increasing as the

economy began to unlock its potential. A more basic issue was the

system of decision-making legitimated by Nkrumah, for which he was held

personally responsible by the bureaucratic elites. Nkrumah saw himself

in the historically appointed task of "sweeping away the fetters on

production", eliminating "feudal elements," and "neocolonialism," so

that the "productive forces of society could be liberated." Ironically,

the new technicians, though they use a different vocabulary, see

themselves as performing the identical tasks, freeing the economy from

the waste and inefficiency spawned by wayward ideologists and corrupt

politicians. In their eyes, Nkrumah had become the chief fetter on the

forces of production.

In many respects, the Army and police are also bureaucracies, their

officers sharing many of the attitudes and concerns of the civil

service. Unlike politicians, neither the army officers nor the

bureaucrats include the art of persuasion in their usual kit of tools.

To govern, however, it is not enough to be "modern-minded" and

incorruptible. The value of the politician lies in his ability to

manipulate opposing factions, and thus mitigate conflict through

compromise. In the absence of the politician's special skill, Ghana's

military government may turn ineluctably to the use of authoritarian

measures, a tendency that would be reinforced by the paternalistic

attitudes of the technocrats.

The regime's general prohibition of political activity and membership

in the Convention People's Party raises the fundamental issue: how to

avoid a gulf between the government and the governed that would compel

the regime to use increasing force to remain in power. The CPP was a

mass party with tens of thousands of members. For the Army to reform

the party is one thing, but to eliminate it altogether is to burn the

bridges between the citizens and the state. Moreover, the National

Liberation Council is heir to the economic frustrations and unfulfilled

popular aspirations of the previous regime. The experiences of military

governments in the Sudan, Burma, and several Latin American countries

suggest that neither the Army nor the bureaucracy can move far toward

fulfilling popular aspirations in Ghana without some form of mass

support. Since the regime cannot maintain itself in power indefinitely

without a social base, to whom will it turn?

Other recent moves cast additional light on the political complexion of

the new regime. Communist aid technicians have been ousted from the

country; trade patterns with the East are being revised; the end of

"disastrous" scientific socialism has been proclaimed; the regime has

jailed several militant intellectuals; the Asantehene and traditional

chiefs have declared their allegiance; and the very name of the

National Liberation Council recalls the name of a former conservative

opposition group, the National Liberation Movement. By themselves these

actions are not conclusive evidence of the nature of the regime. One

could reasonably assume, for example, that any of these moves could

have occurred without demolishing the original framework of government

established by Nkrumah and the CPP.

They assume a different aspect when viewed in context of the regime's

announcement on February 26 that the new constitution of Ghana is to

establish a government based on the separation of powers. The proposal

of a system in which "sovereign powers of the state are judiciously

shared among . . . the legislature, the executive, and the judiciary"

was of course inspired by the constitution of the United States; but

Ghana resembles neither the US today nor the 13 original states of

1787. In the revolutionary American colonies, the separation of powers

was designed not only to ensure personal freedoms, but also to

establish a "negative" government without a social program and endowed

only with limited authority. The system was intended to inhibit the

formation of a tyrannous majority by deliberately pitting faction

against faction; it recognized the existence of antagonistic interests,

and institutionalized them in the government itself.

A formal separation of governmental powers in Ghana would not

necessarily mean that the government will be unable to assert authority

in the hinterland. Nevertheless, to weaken the powers of the central

government in a country where the countervailant forces are hostile to

the state is to engage in an experiment that could imperil national

unity and slow the pace of economic development. A revival or

institutionalization of regional, tribal, and class interests would

alter the evolution of Ghanaian society, and jeopardize the continued

existence of either democracy or stability. If that prospect came to

pass, who would then mourn the passing of the "clown"?

See also: The Men

in Charge

Africa 1966