Kofi Abrefa Busia

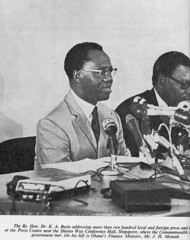

One of my side-projects, much neglected in the years since I came upon this material, is the editing of a collection of the writings of Dr. Kofi Abrefa Busia, the former Prime Minister of Ghana. He lead the country during the Second Republic from 1969 to 1972 and was overthrown by a military coup on January 13, 1972. An eminent sociologist, he had turned to politics out of necessity and his brand of conversational politics has had a lasting legacy in Ghana. His writings however have not been as widely disseminated as they should and, sadly, many are now out of print. The Busia Foundation in recent years has sought to remedy this state of affairs.

Busia interests me as a prime example of Ghanaians as cultural interpreters. His academic career was distinguished and the scholarly works were numerous. Along with the public intellectual persona, there was the family man, the religious man. Of course there was also the politician and his was a lifelong struggle for Ghana. There was the anti-colonial struggle along with J.B. Danquah and others. There was the post-colonial struggle and disappointment - he had to live in exile from Nkrumah's one party rule watching the country decay and his friends and colleagues detained and persecuted. There was the elation of gaining power in 1969 and the promise of putting the country back on the right footing. Then again in the bitterest setback, his government was overthrown and again the sight of the looting and worse of his country in his dying years. His political progeny are currently in ascendance in Ghana and his positions have on the whole been vindicated. Still having foresight and being right in politics while ending up on the "wrong" side is little consolation.

The thread that runs through the writings is the working of extraordinary and methodical mind. One sees the intellectual energy and deep thought of a great academic. It is the sociologist who had keen political instincts and great curiousity. "People matter" was his favourite talking point. He was willing to sacrifice some measure of rapid economic development on the altar of social living. His legacy is about conversational politics, about an openness to participation. There's even the minor controversy he raised about "not ruling out 'dialogue'" with the apartheid regime South Africa. Even if his nuanced position would foreshadow what transpired 20 years later, it was not a popular position for an African head of state in 1971.

In the spirit of Ghana's Jubilee Year, our 50 years of independence, I thought it would be worth sharing a sample of the articles in the collection. I hope you find them interesting. There is much more to say and hopefully this will give me the impetus to find a more fitting repository and bring the project to completion.

A pamphlet written in June 1956 as a companion to the party manifesto on the eve of the elections laying out the NLM's position on the Constitution, raising "the issue of Moral Standards" and questioning the CPP's "unwise and innefficient administration".

"The eyes of the world are upon us; the rest of suffering Africa looks to us for an inspired leadership and we dare not let them down. We must be prepared to give everything, life itself, to ensure that we lay sound foundations for the future happiness, greatness and prosperity of our country. Our independence must have moral foundations on which we can build our heritage of the future."

This November 1956 memorandum lays out the opposition position on "essential safeguards required to persuade northern territories to accept union with the Gold Coast". Written before a debate in Parliament concerning Gold Coast Independence, this prescient piece spells out almost all the pitfalls and temptations that would befall a newly independent Ghana. Simply stated "there is no provision for any checks and balances" in the political structure of the First Republic. All the worries "there should be provisions in the Constitution before Independence to safeguard regional and minority rights" came to nought. Further he noted that "the United Kingdom Government has rejected the suggestion that the new Constitution should make any provisions for individual rights or the rights of minorities". Ghana would pay the price for failing to heed these issues.

A celebrated lecture delivered at the Eighteenth Christmas Holiday Lectures and Discusions for Tomorrow's Citizens organized by The Council for Education in World Citizenship in London on 4th January 1961. A shorter paper later published in United Asia: An International Magazine of Afro-Asian Affairs, distilled the essence of the talk. Here we have Busia as the ultimate cosmopolitan, advocating democracy and methodically taking apart the often spurious arguments of expedience profered about democracy in Africa. This is fairly representative of his style, rebutting at once the opportunists at home and the faint-hearted democrats in the West that chose, then and now, to prop up authoritarian regimes.

On the encounter between Christianity and African cultures. In the International Review of Missions (January 1961).

A heartfelt speech given to a conference of Ghana Students Association of Britain and Ireland (February 29, 1964).

A pamphlet setting out a vision for Ghana and laying into the realities of Nkrumah's rule. December 1964

A short letter in The Friends' Quarterly (January 1965) setting the record straight about the situation in Ghana then at the height of one-party rule.

The text of his speech at the inauguration of the Second Republic of Ghana at the Black Star Square in Accra on 1st October, 1969 when he was sworn in as Prime Minister.

This essay, published in 1979, is taken from a special volume of articles on democracy on the occasion of Werner Kaägi's 70th birthday. Tightly argued, it cogently distills a lifetime of insight on the eternal topic. It is one of Busia's last published works and was written in exile only months before his death in 1978.